The IRS hates casino win/loss statements for two main reasons – one legal and the other practical.

First of all, the IRS has the proper legal authority to disallow the usage of most casino win/loss statements. The Courts and the IRS have interpreted Section 165(d) of the Internal Revenue Code in such a way that gambling activities cannot be reported in a summary fashion. Instead the IRS prefers, yes insists, that gamblers keep a gambling diary (See Revenue Procedure 77-29) and report their activity by “gambling session” (See IRS Chief Counsel Advice Memorandum 2008-011 for more information).

For example, if a gambler has a $10,000 winning gambling session followed by a losing gambling session of $9,900, the gambler is not allowed to merely report the difference of $100. Instead, the gambler must report the $10,000 as other income, and if the gambler itemizes his deductions, then the loss of $9,900 is included as an other miscellaneous deduction not subject to the two percent limitation.

The take away – IRC Section 165(d) is focused on “transactions” and not “totals.”

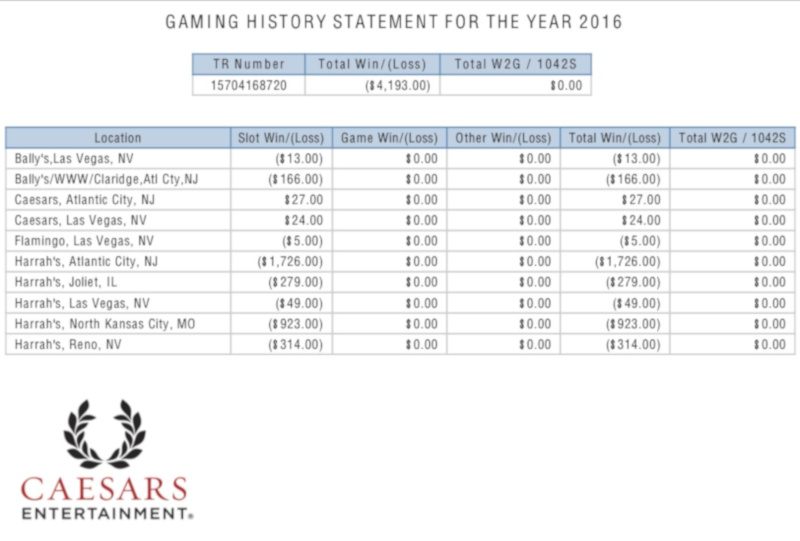

The second reason is indeed more practical. How can the IRS verify that the amounts reported in a casino win/loss statement? Or more likely, how can the gambler during an audit prove the amounts stated in the casino win/loss statements? Not very easily.

It is important to understand the source of the amounts used on casino win/loss statements. For slot machine players, the amounts are recorded when a gambler uses a Player’s Card. For table games such as poker and black jack, the amounts are frequently estimated by a “pit boss” while observing the gambler on the casino floor.

For slot machine players these methods, naturally lead to three common questions:

- Can the gambler prove that he used the Player’s Card every time he gambled?

- Can the gambler prove that he only played one slot machine at a time?

- Can the gambler prove that he was the only one that used the Player’s Card?

For question #1, it is difficult to convince an IRS auditor or a judge that someone not able to keep proper records in the first place was able to remember to use their Player’s Card every time they gambled.

Question #2 is a fair question. It is common technique for slot machine players to simultaneously play adjacent machines. Unfortunately, it is not possible to insert a Player’s Card into more than one machine at a time.

Regarding question #3, it is important to note that casinos strongly discourage gamblers from sharing their Player’s Card – but it is not uncommon or impossible. The IRS faced a similar situation in the case of Pan v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, T.C. Memo. 2011-40, (U.S. Tax Ct. 2011). For the tax year in question, the casino reported several Form W-2G’s in Mr. Pan’s name to the IRS. During the audit, the IRS included these additional amounts in Mr. Pan’s income. Eventually, Mr. Pan was able to provide his passport to the IRS and demonstrate to their satisfaction that he was indeed out of the country when some of the W-2G’s were generated. But the question remains. If, if someone is able to “forge” another person’s identity when they receive a hand-paid jackpot, how hard is it to “borrow” another gambler’s Player’s Card?

If that was not reason enough, almost all the casino win/loss statements have some type of “disclaimer” language discouraging their use as reliable accounting records.

For these reasons and more, it is not surprising that the IRS HATES casino win/loss statements.